Understanding and Supporting Bone Health

Bone health refers to the strength, structure, and resilience of the skeleton that carries us through every movement we make. Bones look solid from the outside, but internally they behave like living tissue. They respond to hormones, nutrients, movement, and aging. That means bone health is not fixed. It is continually shifting, and we have real influence over how strong our bones remain throughout life.

Why Bone Health Matters

Bones provide support, protect vital organs, store minerals, and serve as the framework for muscles to move. When bone density declines, the entire system becomes more fragile. Fractures become more likely, especially in the hip, spine, and wrist. This can dramatically affect quality of life.

Bone is always changing. From childhood through our late twenties, the body focuses on building bone. This reaches a peak called peak bone mass. After that point, bone is maintained through a balance between cells that build bone (osteoblasts) and cells that break it down (osteoclasts). In younger adults, the two stay fairly even. With age, especially in women experiencing menopause, the balance shifts and bone loss becomes more common.

Who Is at Greater Risk for Bone Loss

Bone loss is influenced by many factors. Hormonal changes, particularly the decline in estrogen during menopause, accelerate bone breakdown. Men can experience bone loss as testosterone decreases. Additional risk factors include family history of osteoporosis, low body weight, chronic steroid use, smoking, excessive alcohol intake, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and nutrient deficiencies. People with limited sun exposure or low dietary intake of calcium, magnesium, protein, or vitamin K are also more susceptible.

How Bone Mineralization Is Assessed

The most widely used tool to measure bone density is the dual energy X ray absorptiometry scan, commonly known as a DEXA scan. It measures bone mineral density in the hip and spine and provides T scores that compare a person to the peak bone mass of a healthy young adult. Lower T scores indicate greater risk for osteoporosis.

Beyond imaging, several lab markers can help evaluate bone turnover. These include serum vitamin D (25 hydroxyvitamin D), parathyroid hormone, calcium, magnesium, and markers of bone turnover like CTX and P1NP. When interpreted together, these markers offer a more detailed picture of how actively bone is being built or broken down.

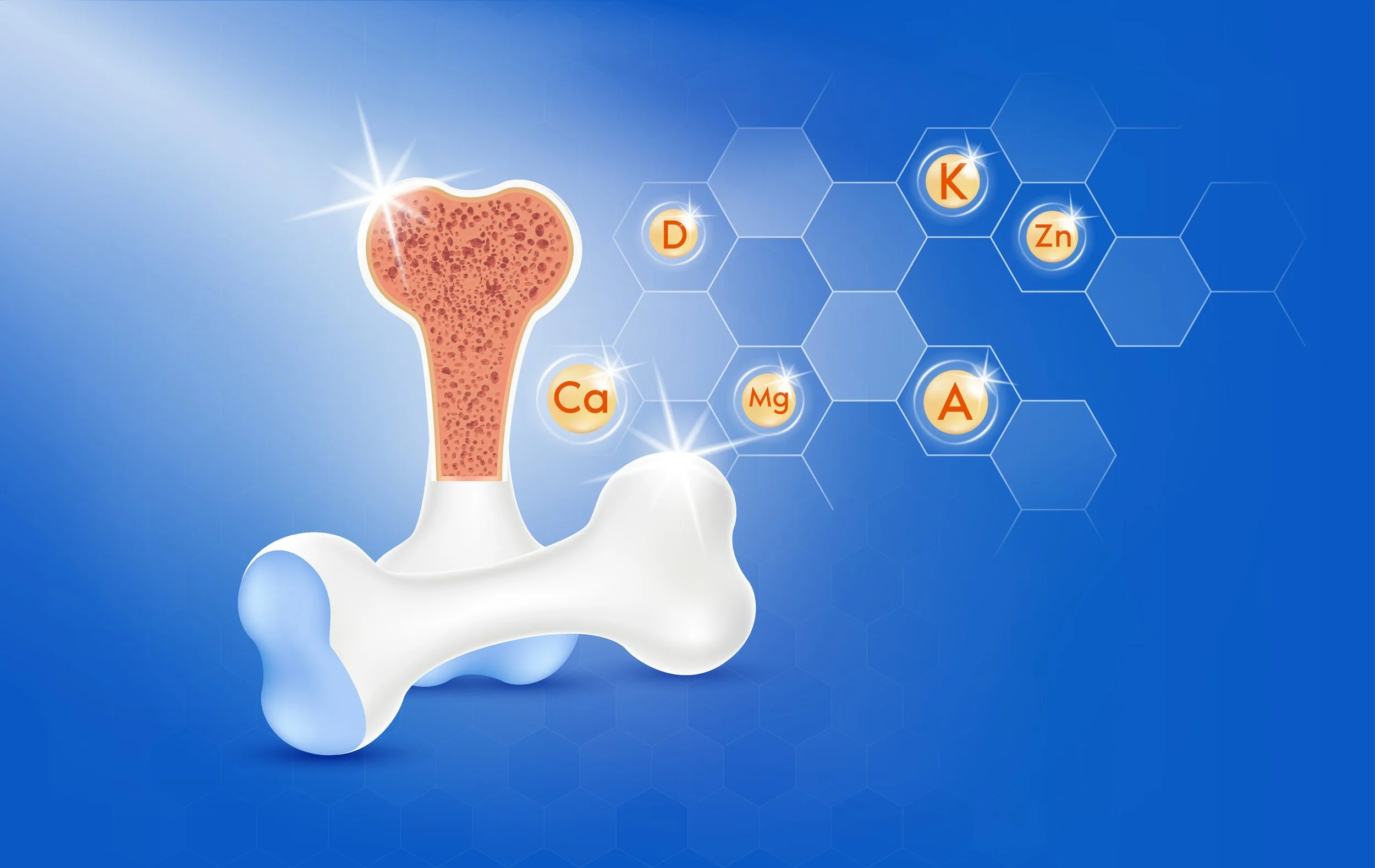

Nutrients That Influence Bone Strength

Bone formation depends on an intricate interplay of nutrients.

Vitamin D helps regulate the absorption of calcium and phosphorus, which are essential for mineralizing bone. Research consistently shows that vitamin D deficiency increases fracture risk (Holick 2017). Optimal functional levels for 25 hydroxyvitamin D are typically considered around 40 to 60 ng per mL for skeletal support.

Calcium is the primary mineral that provides hardness and structure to bone. It works together with phosphorus to create hydroxyapatite, the crystalline framework that gives bones their density. When dietary calcium is low, the body pulls it from bone to maintain normal blood calcium levels. Over time this weakens the skeleton. Although dairy products are well known calcium sources, many plant based foods contribute meaningful amounts. Sesame seeds, chia seeds, sardines, tofu made, and leafy greens can all support daily calcium needs. This is especially helpful for individuals who do not consume dairy.

Magnesium participates in over 300 enzymatic reactions and plays a crucial role in converting vitamin D into its active form. Low magnesium levels are associated with reduced bone density and increased fracture risk (Rosanoff et al. 2021).

Vitamin K, particularly K2 in the form of MK7, activates osteocalcin. Osteocalcin is a protein that binds calcium to the bone matrix. Without vitamin K, calcium regulation becomes inefficient and bone mineralization suffers (Khalil et al. 2020).

Additional minerals include phosphorus, zinc, boron, and trace minerals like manganese and copper. These support the structural matrix and enzymatic processes that allow bones to stay strong.

How Movement Influences Bone Remodeling

Bone strength depends heavily on mechanical stress. Weight-bearing exercise creates tiny vibrations and pressures within the bone. These signals activate osteoblasts. Osteoblasts are bone building cells that produce collagen and minerals to form new bone tissue. They work alongside osteoclasts, which are cells that break down old or damaged bone. Ideally, the two stay in balance. When osteoclast activity becomes too dominant, bone loss results.

Resistance training, plyometrics, brisk walking, stair climbing, and even dancing can stimulate osteoblasts and support bone density. Research supports exercise as one of the most powerful non-pharmaceutical tools for preventing osteoporosis (Zhao et al. 2015).

Helpful Supplements for Bone Support

Some individuals benefit from targeted supplementation, especially when dietary intake is low or absorption is impaired. Supportive options include:

· D3 +K2 which work together to support calcium absorption and direct calcium into bone rather than soft tissues.

· Whole Body Collagen which supplies amino acids used by osteoblasts to build the collagen matrix of bone.

· Trace mineral blends that replenish small but essential minerals used in bone remodeling.

· Calcium and magnesium, ideally in balanced and well-absorbed forms.

Supplementation is most effective when built on a foundation of nutrient-rich foods. My work focuses on helping you optimize your diet so that your daily meals naturally support healthy mineralization.

Bringing It All Together

Bone health is dynamic. It involves hormones, nutrient status, mechanical stimulation, and genetics. By understanding these mechanisms, you can make informed choices that help maintain strong bones throughout life. Supporting bone health is not only about preventing disease. It is about preserving mobility, vitality, and confidence as the years go by.

If you want to improve your bone density, nutrition is one of the most powerful tools available. I can help you identify nutrient gaps, optimize your labs, and build a lifestyle that protects your bones long term.

References

Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553.

Rosanoff A, Dai Q, Shapses SA. Essential nutrient magnesium and the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Nutrients. 2021. doi: 10.3390/nu13062056.

Khalil RB, Zarour S, Touma Z. Vitamin K2 in bone metabolism and osteoporosis. Rheumatology International. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00296 020 04657 6.

Zhao R, Zhao M, Xu Z. The effects of differing resistance training frequencies on bone mineral density in women. Medicine. 2015. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002210.