Microbiome 101: Understanding your Inner Ecosystem

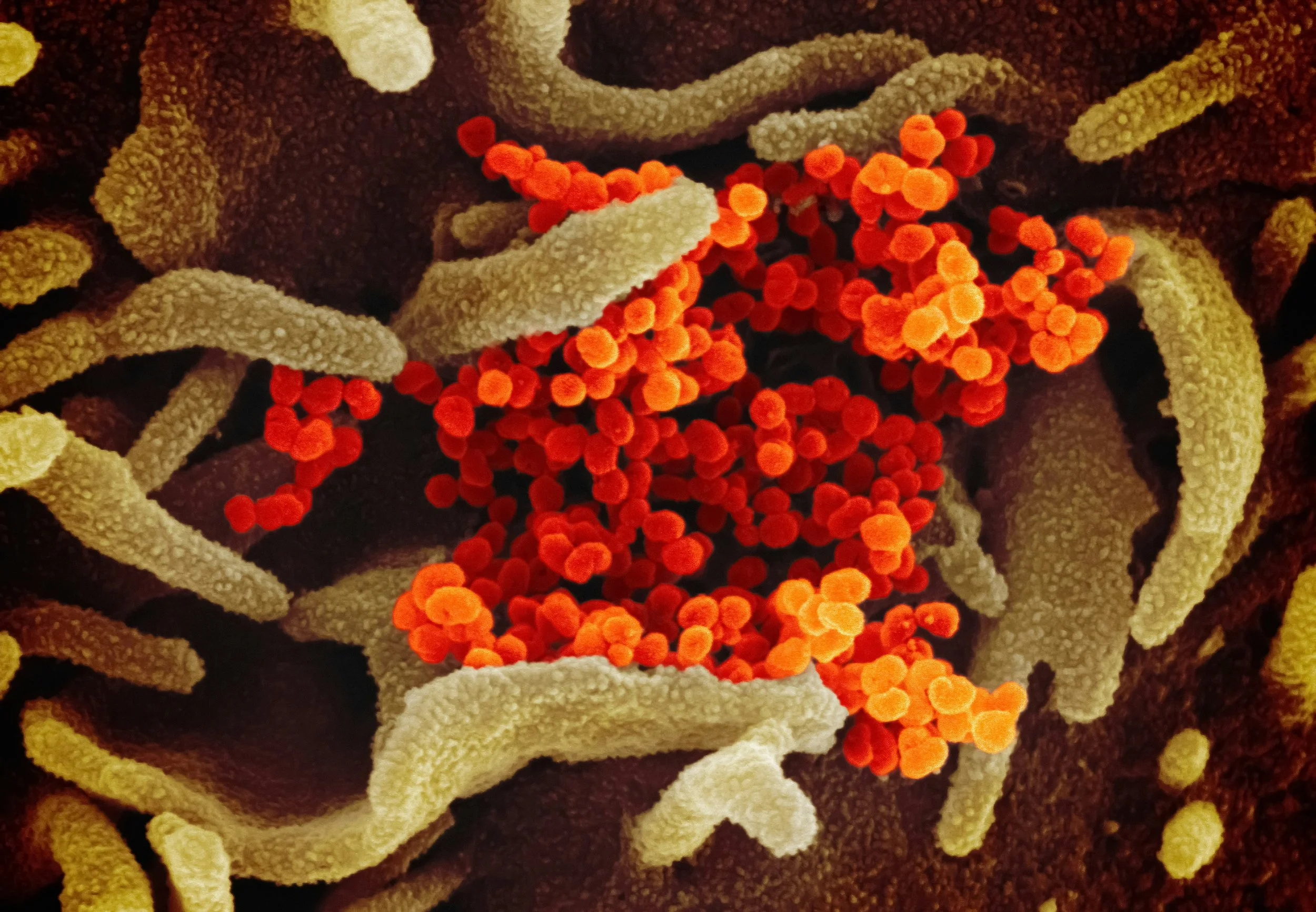

The gut is home to one of the most extraordinary ecosystems on Earth. It is a busy, living community made up of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microbes that work together in ways that influence almost every aspect of health. Scientists call this entire community the microbiome, and the portion that lives inside the intestinal tract is known as the gut microbiome. Think of it as a densely populated neighborhood where each resident has a job, a personality, and a preferred type of food.

What is a microbiome and what is the gut microbiome?

A microbiome is a collection of microorganisms and the genetic material they contain. Every environment, from soil to oceans to the surface of your skin, has its own microbiome. The gut microbiome specifically refers to the trillions of microbes that live inside the digestive tract, primarily in the large intestine.

This community is not passive. It acts almost like another organ system with its own metabolism, communication networks, and chemical output. Researchers estimate that the gut microbiome contains more genes than the human genome by a factor of about 100 to 1. That means it is capable of producing many compounds that the human body cannot make on its own.

The gut microbiome has many essential functions

The microbiome influences nearly every major physiological system. A few well-studied functions include:

Digestion and nutrient production.

Gut microbes help break down complex carbohydrates, fibers, and polyphenols that human digestive enzymes cannot process. In doing so, they create beneficial molecules such as short-chain fatty acids. Certain microbes also synthesize vitamins, including vitamin K2 and several B vitamins.

Immune regulation.

About 70 percent of the immune system sits along the gut lining. Microbes help train immune cells, promote immune tolerance, and reduce excessive inflammation. Balanced microbial communities are associated with lower risk of autoimmune activity.

Gut barrier integrity.

The intestinal lining is a selective barrier that protects against pathogens while allowing nutrients to pass through. A healthy microbiome supports this barrier by producing compounds that keep the intestinal wall strong and less permeable.

Metabolism and blood sugar control.

Research has shown that gut microbes influence insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism, and appetite regulation. Imbalances can contribute to metabolic dysfunction.

Brain and mood.

The gut communicates with the central nervous system through what scientists call the gut brain axis. Gut microbes produce neurotransmitter precursors and influence stress hormones and inflammatory signals. This is why changes in the microbiome can affect mood and cognitive function.

How food choices shape the microbiome

Diet is the single most powerful influence on microbial composition. What you eat feeds either beneficial or harmful bacteria. Every meal sends a signal to the gut ecosystem.

Fiber.

Soluble fibers found in vegetables, fruits, legumes, oats, and seeds are the preferred food source for many beneficial bacteria. These fibers are fermented in the colon to produce short chain fatty acids. Diets high in varied plant fibers are consistently associated with greater microbial diversity and improved metabolic markers.

Polyphenols.

Colorful plant foods contain polyphenols which cannot be fully digested without microbial help. Microbes transform polyphenols into antioxidant and anti inflammatory metabolites. Foods such as berries, olives, green tea, cocoa, and herbs support this process.

Protein and fat.

Protein and fat influence the microbiome indirectly. Excessive intake of certain animal proteins can promote bacteria that generate potentially harmful metabolites such as trimethylamine oxide. However, balanced intake of lean proteins does not appear to harm microbial diversity. Healthy fats from extra virgin olive oil, nuts, seeds, and fish tend to support more beneficial communities.

Artificial sweeteners and ultra processed foods.

Several studies show that emulsifiers, certain artificial sweeteners, and highly processed foods can shift microbial communities in a less favorable direction. These changes may promote inflammation and glucose intolerance in susceptible individuals.

Key microbial strains and what they do

The gut contains hundreds of species, but a few genera are consistently studied for their roles in health.

Bifidobacterium.

Important in early life and throughout adulthood. Helps break down fibers, lowers intestinal inflammation, and supports bowel regularity.

Lactobacillus.

Produces lactic acid which helps maintain a healthy pH. Supports the immune system and produces antimicrobial substances that protect against pathogens.

Akkermansia muciniphila.

A species associated with improved metabolic health. It plays a key role in maintaining the gut barrier by interacting with the mucus layer that lines the intestines.

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii.

One of the strongest producers of the short-chain fatty acid butyrate. Lower levels are linked with inflammatory bowel conditions.

Science is still uncovering the functions of many species, and not all strains behave the same way in every person. Genetics, diet, medications, and environment all shape the microbial landscape.

Short-chain fatty acids and why they matter

Short-chain fatty acids are produced when microbes ferment fiber. The three major ones are acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These compounds support health in multiple ways:

• Butyrate is the primary fuel source for colon cells and helps maintain the gut barrier.

• Acetate helps regulate appetite and influences lipid metabolism.

• Propionate supports blood sugar balance and reduces liver fat production.

Short-chain fatty acids also have systemic anti-inflammatory effects and help regulate immune activity. Low fiber diets lead to lower short-chain fatty acid production, which can weaken the gut lining and increase inflammation.

How supplements can support the microbiome

Food should always be the foundation, but certain supplements can offer targeted support when used appropriately and backed by evidence.

Probiotics.

Live beneficial bacteria that can temporarily change microbial activity. Effects depend entirely on the strain and dose. Some strains such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG have strong research for immune support, while others support bowel regularity or reduce antibiotic associated diarrhea.

Prebiotics.

These are fibers or compounds that feed beneficial bacteria. Examples include inulin, fructooligosaccharides, and partially hydrolyzed guar gum. Prebiotics consistently increase short chain fatty acid production and support microbial diversity.

Polyphenol extracts.

Extracts from pomegranate, grape seed, or green tea can enhance microbial metabolism and promote growth of beneficial species by providing substrates that microbes transform into antioxidant compounds.

Digestive support supplements.

Compounds such as digestive bitters, ginger, or enzymes can improve upper digestive function which indirectly benefits the lower gut by ensuring that food is broken down properly before reaching the colon.

No supplement can compensate for a diet low in fiber or high in ultra processed foods, but supplements can be useful tools for targeted support.

Bringing it all together

The microbiome is not a mystery once you understand that it behaves like a living ecosystem. Feed it well, keep it diverse, and it will return the favor by supporting immune strength, metabolic health, mood balance, and long term wellness. Small and consistent dietary choices are the most powerful way to shape this inner community.

References

• Valdes A et al. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2179

• Thursby E and Juge N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochemical Journal. 2017. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160510

• Koh A et al. From dietary fiber to short chain fatty acids and their impact on host physiology. Cell. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041

• Sonnenburg ED and Sonnenburg JL. The ancestral and industrialized gut microbiome. Science. 2019. doi: 10.1126/science.aau5812

• Zmora N et al. Personalized gut mucosal colonization resistance to probiotics. Cell. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.041

• Depommier C et al. Supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila in overweight and obese adults. Nature Medicine. 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41591 019 0495 2

• Singh RK et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12967 017 1175 y